contextualization. This is something present in Japanese. For those who have been studying Japanese for some time, this is nothing new. Now, for those who just started, here's a warning: Context is everything in the Japanese language.

The Japanese language is highly contextual. It's hard to know how to say something in Japanese unless you know the details of the social context. And that reflects a long-standing preoccupation with order, hierarchy, and consensus.

To be honest, this is one of the reasons why Japanese is a difficult language. Because it is a severely contextual language, sometimes a dialogue in Japanese can end up being something quite ambiguous and open to interpretation by others.

Índice de Conteúdo

Is context in Japanese such a difficult thing?

When translating something into Japanese, you often need to know: the time of day, the time of year, the formality of the situation, the age, the gender, the social status of the speaker, the age, the gender, the social status of the recipient, the age, gender and social status of any third party mentioned, the gender and then the social connections between the speaker, listener, gender and third parties. Are they family members? Do they work for the same company? Did I mention that you need to know the gender?

Unlike English, or even Portuguese, where the level of formality is quite simple, in case it is something quite necessary, which is rare by the way. Even more so in Brazil, we don't have a headache in relation to social hierarchies, age, sex, etc.

When we communicate, we don't have multiple ways of saying "you". "You" It's a word that can be used on virtually any occasion, with anyone. Does not exist "polished form" and "casual way" in verbs. You don't have to change the "way to talk" depending on the person because in English there is no such thing. At most, you refer to a stranger with "Sir" or "Madam". This is accompanied by a "please", "thanks" and "excuse me". Only.

It gets even more complicated when in Japanese, you have to "read between the lines". This is something quite common among the Japanese. "Read between the lines" It's the hardest part of Japanese. It's like walking on thin ice. Wrote, not read, the dick ate.

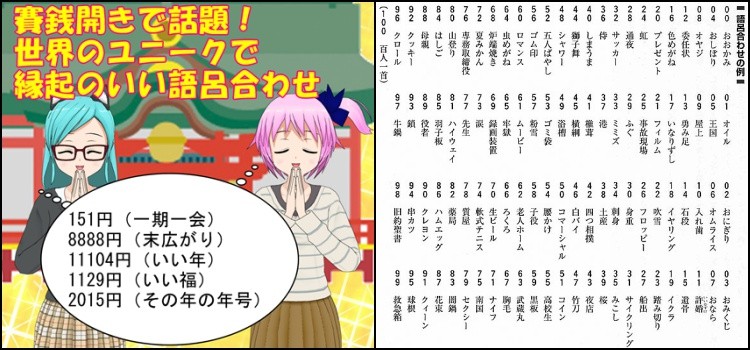

Let me give you some concrete examples of how contextualization works. We can think of each speech situation as having a position on two axes. One is the axis of the social hierarchy.

Some people are above the speaker and some people are below the speaker. The second axis is formality. Almost every Japanese verb is different based on these two aforementioned axes. In fact, Japanese adjectives and many nouns also vary based on these two axes.

Contextualization within Japanese verbs

Let's analyze the following situation: A group of college friends get together for a drink, and one of them says:

"Hey, I saw our favorite teacher, Professor Tanaka, the other day."

Well, clearly the situation between friends is informal, but Professor Tanaka is the social superior of all friends. As a result, the speaker's language should be honorific but informal.

So to say that "saw Professor Tanaka", it is not enough to simply say "田中先生を見た" (tanaka sensei wo mita / saw Professor Tanaka). will have to say "田中先生にお目にかかった"Sorry, I can't fulfill that request. Literally, the phrase means "My eyes fell on Professor Tanaka." But, translated in this context, the phrase means "I saw Professor Tanaka."

By now, you might be thinking: "Wow, the Japanese like to complicate things."

However, while there are things that are simplified in English but complicated in Japanese, the opposite is also true.

Example of this: Let's take the phrase "Although the live octopus was delicious, it didn't want to be eaten." That same sentence in Japanese would be: "美味しおかったが食べられたくなかった" (oishiokatta ga taberaretakunakatta). Literally, "It was delicious but I couldn't eat it".

So it is. The sentence in question may seem a bit ambiguous, however, this would be the answer to the question: "Did you eat the octopus alive?" ***(生き作りを食べたますか)

So it is. Did you notice that in the original Portuguese sentence, a lot of words had to be used? In Japanese, things became more simplified. Even more so when the subject who would be the "live octopus". Well, this is quite common in the Japanese language. When you understand who the subject is, the Japanese don't mention the subject. Because for them, mentioning the subject is very redundant.

Okay, to recap. Japanese is highly situational and nothing – not even pronouns or adjectives – are socially neutral. Extreme care must be taken when speaking to someone in Japan. After all, you don't need much to do poorly in a social situation. Just use the wrong word.

*** The term "生き作り" (ikitsukuri) does not necessarily mean "live octopus" but rather, a common dish in Japan that is sashimi served alive. But the dish can also be served with octopus, shrimp or lobster.